We all know what URLs (Uniform Resource Locator) are; put in popular jargon, a URL is the address to a web page. URIs (Uniform Resource Identifier) are similar to URLs but are one level above; URIs point to a resource and are less strict than URLs. While a URL must started in http://, a URI can be ftp://, in URN format, or even relative. Think of a URI as a URL but more; every URL is a URI but every URI is not a URL. One thing that separates URIs from URLs is URIs can hold data in and of themselves — a “data URI”. While a URL must resolve with a server for you to get any data, a data URI can load in your browser and make no outside connection because all the data needed is stored in the URI. Why is this important? Because, according to a study by Henning Klevjer of University of Oslo in Norway, URIs themselves can be malicious.

Now you must be thinking “Ashraf is talking about a malicious link which means a link that takes you to a malicious website with malicious content”. No, I’m not. As I just mentioned URIs have a unique characteristic of being able to hold data. Klevjer asserts this characteristic makes it possible for URIs to be malicious in and of themselves.

According to Klevjer, it is possible to create a phishing website — using images, text, etc. — then use Base64 to encode the content and store it in a URI. When someone visits the URI in their browser, the URI decodes and loads the phishing “website” and the end user likely doesn’t even know he or she isn’t at a real website. The difference here between a phishing URI and a phishing URL is a phishing URI makes no outside Internet connection; all data for the phishing “website” is stored locally in the URI. Since no outside Internet connection is made, many anti-phishing security tools will not block the “website” because, as far as the security tool is concerned, the user never loaded any website. In other words, website-less phishing.

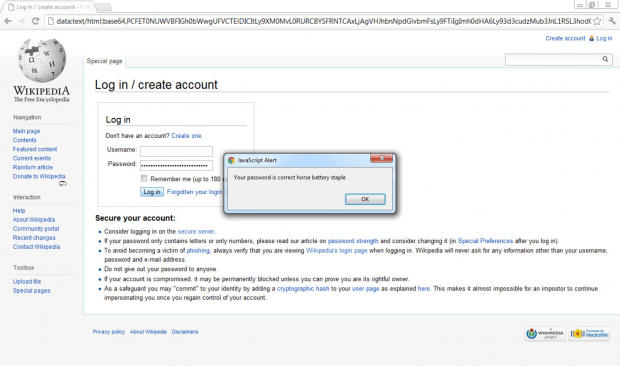

In his paper Klevjer provides a proof-of-concept by developing a URI that loads a fake Wikipedia login page:

As another security researcher Johannes Ullrich points out, scumbags using URIs for website-less phishing still need some sort of way to get data attained from phishing targets out to their servers. But, as Ullrich says, this shouldn’t be too hard with clever hackers using DNS requests to transport the data into log files of remote servers.

While Klevjer focuses on website-less phishing with URIs, his colleague Per Thorsheim points out that URIs can contain small malware, too, such as infected Java applets. In other words, not only can URIs be used for website-less phishing but they can, literally, be malware on their own.

The one thing working against URIs is length. Any URI containing an encoded website or file will be huge in length. The above-mentioned proof-of-concept Wikipedia URI is 24,682 characters long. The length, and weird formatting of data URIs, is likely to scare potential targets away from clicking. However, as Klevjer points out, the rise of URL shorteners (e.g. bit.ly) makes this a mute issue: throw a data URI into a URL shortened and a long, scary data URI turns into a short, pretty URL. In the case of Klevjer, he turned his 24,682 character URI into a 26 character URL.

While the thought of having links being malicious in and of themselves is a scary thought, there is a bright side.

The bright side is some modern browsers either limit the length of URIs or don’t load them at all. For example, Klevjer says in his tests Internet Explorer 9 refused to load his 24,682 character URI because of its length while Chrome blocked the redirection to a data URI. Firefox and Opera, however, loaded the data URI without so much as a hiccup

Moral of the story? If you see an ugly, long string of text don’t click on it, and think twice before clicking on a shortened URL.

[via Sophos]

Email article

Email article